|

|

There is perhaps no debate that departs as quickly from what we actually know into what we would actually like to be true as in the topic of: life beyond the Earth. One reason for general confusion when it comes to the science of astrobiology (a field, as Professor Joe Wolfe has put it: “yet to prove the existence of its subject matter”) is that it really is very difficult to learn enough to have an informed opinion. This is because astrobiology truly is interdisciplinary: it requires an almost expert level appreciation of fields as diverse as astrophysics and planetary sciences, an understanding of plate tectonics and geology more broadly, chemistry – specifically biochemistry but also physical chemistry of redox reactions, some genetics thrown in for good measure and not least evolutionary biology.

To get across all of this is difficult indeed and most who do when confronted with the question about whether or not they believe there is intelligent life out there are reticent to venture an opinion.

So let us leave the experts to one side for the moment – and return to them later and consider what your typical educated lay-person – perhaps even someone with a science degree – thinks about the possible existence of aliens. Typically, although of course not always, the thought is this: the universe is so vast it is almost inevitable that we humans are not alone. A casual appreciation of astronomy introduces one to some truly vast numbers: 200 billion to 300 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy alone…and some 200 billion galaxies in the observable universe (in a universe that itself might be infinite). Such staggering numbers seem to suggest that if we were to be quite conservative and assume only 1 out of every billion stars has an Earth-like planet orbiting it where the conditions are just right, this suggests that there are 200 such planets in our galaxy alone…and 200 times 200 billion such worlds in the universe. But each week seems to bring news of more discoveries on the “exoplanet” front – we learn about super-Earths and planets in their host star’s “habitable zones”. It seems to be only a matter of time before we are going to actually see some alien craft in orbit around an alien world. These supposedly huge numbers of habitable worlds make it seem inevitable that once life gets going on a world, intelligent critters will arise as well…just as they did here on Earth. If you hope one day that aliens will be found, then this straightforward analysis makes things seem rather promising, doesn’t it?

It doesn’t – because there is a huge flaw in the argument. And it has nothing to do with astronomy and everything to do with biology.

Why, so far, has the “Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence” (SETI) so far found nothing? Here is one obvious answer: because there is nothing to find. Their aim is to find intelligent life in the universe – but of course what that really means is life capable of transmitting radio signals of the sort SETI is able to detect. But SETI can go on forever searching even if it finds nothing because it seems to be testing a hypothesis that is not falsifiable. The hypothesis “There exist intelligent aliens” is not falsifiable. It belongs to that class of statements that all religions share: “X exists”, all of which are not falsifiable. No experimental test can ever demonstrate that aliens do not exist because no search could ever be exhaustive. This being the case, the argument against the idea that there are intelligent aliens out there can never consist of direct evidence, not strictly because such evidence is lacking but rather no conceivable observation could ever be made which would constitute evidence of that sort.

But this does not mean the search has no merit. It does. The science of what to look for and how to look for it and where help propel science forward on many fronts. And the hypothesis “There exist no intelligent aliens capable of transmitting radio signals” is scientific and anyone who suggests that hypothesis is correct can be shown to be wrong by observation.

There have been many books written about the likihood of intelligent life elsewhere that we might be able to detect. Popular culture in the form of just about every science fiction book or movie ever created reinforces the idea that the galaxy might be teeming with aliens. But what about the other side of the argument? The sceptical, scientific side? One view is ventured by planetary scientists Ward and Brownlee in their volume “Rare Earth” which lays out the observations which, taken together constitutes a refutation of the popular conception of alien intelligence being ‘out there’. These refutations are collectively the basis of the position which argues that conditions required for intelligent life to arise are likely going to resemble those found on Earth, and places like Earth in the universe are likely very uncommon. This, the “Rare Earth Hypothesis” and anyone who wants to participate in an informed discussion about the possibility of intelligent life out there beyond the Solar system would do well to be familiar with at least some of these points.

Rare Earth Factors

Ward and Brownlee present a list of fortuitous circumstances that have led to the evolution of intelligent life here on Earth. It is this list that attempts to chip away at that amazingly promising billions of possible Earth-like planets that are supposedly “out there” upon which life and intelligence might arise. Ward and Brownlee present the case that life is likely going to be common in the universe and at first glance this would seem to run counter to their entire position. However, as others wish to suggest also – the appearance of microbial life indicates little about the chances of finding complex life. The conditions under which simple life can flourish we shall see are wide ranging. However, our knowledge of more complex biology suggests that animal life (especially) of sufficient sophistication that it can build a radio telescope can only survive in a far more narrow range of habitats. And importantly, there must be selection pressures which coerce evolution into following a path towards increasing complexity – but evolution must not be frustrated by geological or astrophysical events. So it is that Ward and Brownlee consider how distance from the sun and centre of the galaxy (habitable zones), extinction events – from asteroid impacts, to ice-ages and supernovae, plate tectonics (a central theme of the book) and the peculiar characteristics of this solar system (a Jupiter sized-planet and a large moon around the Earth) all come together to provide all-but-necessary if not sufficient conditions for life to begin, evolve and flourish over the billions of years it takes to permit natural selection to spit out something that is able to begin comprehending the whole she-bang.

The Rare Earth Factors (p. xxxi of Rare Earth) suggest that there is something fundamentally flawed about the argument presented in the first part of my introduction. The Rare Earth Hypothesis attempts to solve physicist Enrico Fermi’s paradox about aliens: If they are as common as that argument suggests, where are they? (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004). Indeed, per Fermi, if there is intelligent life in the universe then it would be utterly fantastic to assume that it has evolved at precisely the same time as intelligence here on Earth and so, if it can be detected by a SETI-type program then it is likely to be far more advanced – millions or perhaps even billions – of years ahead of us. And if that is the case, then it should have colonised the entire galaxy and it should be a trivial matter to detect because of its ubiquity (in much the same way as life here on Earth is so easy to detect because evidence of it is everywhere). However, we have not detected alien life, therefore it cannot be that common and so it cannot be millions of years “ahead” of us. Of course this itself may explain the null result in that a civilisation which is that far ahead of ours might “have no more interest in communicating with us than we have in talking to bacteria.” (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004 – p 299). This is a common objection to which I venture the rejoinder that we humans do try to communicate with “lower” forms of life routinely: be they other primates (whom we even teach sign language to) or whales (where we try to understand their songs) or even our pets whom we teach to obey our commands. Indeed the relationship between humans and other life forms seems to be that where we can develop a method of communication, we pursue it. Our inability to “communicate” with bacteria is less to do with our unwillingness to try as our taking seriously our theories about bacteria and what the word “communication” means. It might well be argued that antibiotics are very much an attempt to communicate a message: if you are a parasitic bacteria: stay out of human beings. Hence, I think that the analogy about aliens not wishing to communicate with us is because it would be somehow like us wanting to communicate with bacteria is false.

Some commentators to be discussed later – importantly Lineweaver – seem to suggest that Fermi’s paradox is answered by appealing not so much to physical, chemical and geological factors as to evolutionary ones. Indeed when talking large numbers, “biological” is a prefix that should indicate quantities that are greater than any described as “astronomical”. The “200 billion” (plus!) stars in the Milky Way, multiplied by the “200 billion” or so galaxies in the universe may seem “astronomical” but when one considers the chance evolutionary occurrences that have led to intelligence here on Earth…that number simply is no where near big enough to do the job of guaranteeing that ET is out there somewhere listening for our radio signals. Importantly, Lineweaver has some important observational data on his side when it comes to assessing the likelihood of intelligence elsewhere in the universe. However, prior to considering the chances of intelligent life, let us first consider some of the conditions thought necessary for any life at all to arise. We will begin with a discussion of places in the universe where biogenesis is able to occur.

Habitable Zones

The notion of a habitable zone turns in large part upon the restrictions one places upon the requirements for life. The more we learn about life, the more we seem to broaden the possibilities for locations which are “friendly” towards life. Ward and Brownlee devote Chapters 2 and 3 of their book to a discussion of habitable zones, so in this section I will briefly distinguish between circumstellar habitable zones (CHZ)* and galactic habitable zones (GHZ) and finally explain how the habitable zones for simple life – especially so-called extremophiles might be far broader than normally assumed while the habitable zones for “intelligent” complex creatures capable of interstellar communication and/or travel are likely to be far more narrow. As well as zones habitable in certain regions of space there may also only be some zones habitable in time.

*Ward and Brownlee use “CHZ” to refer to the “Continuously Habitable Zone” – that zone around a star in which a planet’s water will not, over a reasonably long period of time, boil away. For reasons of simplicity, my “CHZ” implies “continuously” as part of the definition of “Circumstellar Habitable Zone” as explained in the next section

The Circumstellar Habitable Zone (CHZ)

This is often the first point of entry for discussions about how much rarer Earth may be than is commonly thought. One of the most important factors in finding complex life in the universe is likely to be whether or not liquid water is present on the surface of a planet. For a number of reasons, liquid water seems to be the best solvent for the chemistry of life to occur in. Whatever the solvent is going to be, it should be both simple and common – water being 2-parts the most common element in the universe by any measure and 1 part oxygen (the third most abundant element in the universe, by mass, after helium) satisfies both of these criteria. Fortuitously, this chemical is a liquid over a range of temperatures unrivalled by almost any other: 100K. This is far broader than other “competitors” such as ammonia and (say) methane (45K and 22K respectively). Only ethane, which is a liquid over 95K, comes close – but it is both more complex, non-polar and with a very low boiling point. Boiling point is, of course, an important consideration for reaction rate is proportional to temperature reaction and so determines how quickly (or otherwise) the production of the requisite chemicals (such as protein synthesis and replication) and evolution occurs. Reactions in non-polar substances like ethane or methane take place over time frames that are orders of magnitude greater than the time taken for similar reactions to occur in an aqueous medium – if they can even occur at all. Water’s boiling point is far higher even than comparable hydrogen-bonded solvents such as ammonia. For these reasons and many others (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004, provide a comprehensive discussion), liquid water seems to be a prerequisite for complex life. As such, any planet on which we look for life must not be so close to its home star that all possible oceans, lakes and ponds are boiled away nor so distant that it is frozen solid to the core.

The CHZ is thus defined as being the range of distances from a star “for which liquid water can exist on a planetary surface” (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004). Importantly, the habitable zone moves as a star ages. Indeed, it will in general move away from a star as, over time, a star’s luminosity increases. This means that an important restriction upon whether or not a planet may harbour complex life that requires liquid water is to consider whether the planet is not simply within the CHZ at some given time, but rather that it is in what is referred to as the “continuous” CHZ; that is, the region around a star where liquid water could persist on the surface for some very large portion of time – likely billions of years if the evolution of life on Earth is any benchmark. For many stars this continuous CHZ is going to be narrow indeed due to the fact that many stars have shorter lifetimes than the sun.

Many stars (approximately half) exist in binary systems. It is likely to be the case that planets in orbit around binary stars are going to suffer severe perturbations, at times, of their motions. This could mean they spiral into their host stars, be flung into outer space or simply drift out of the CHZ. For all of these reasons, this entry point into discussions about how rare Earth is likely to be must necessarily begin with an acknowledgement that this most basic assumption: the fact that the Earth is in an almost perfect Goldilocks-zone around the sun is a situation that is going to be rare indeed.

Against the Rare Earth Hypothesis, some more promising arguments may be found with regards to the “narrowness” of CHZs when considering Red Dwarf stars in particular. Guinan & Engle (2009) suggest that because Red Dwarfs have a lifetime of some 50 GYrs, then even given that the CHZ is within the range of 0.05AU – 0.4AU of the host, the chance of finding conditions favourable to a long and rather tranquil stretch of time in which life can arise around such a star might be quite high indeed. Because Red Dwarf stars are by far the most numerous in the galaxy, any assessment of the constraints considerations of the CHZ place upon chances for finding life, complex or otherwise, outside the solar system, must include some analysis of the conditions which exist in the CHZs around Red Dwarfs. Guinan & Engle answer the most obvious question an astrobiologist would have about habitability of planets around such stars: if they are in the habitable zone, then would they not be tidally locked? They would be, grant Guinan and Engle, however “a thick enough atmosphere (P > 0.1 bar) is capable of transferring heat from the star-lit side of the planet to the dark hemisphere, preventing atmospheric collapse and possibly moderating the global climate.” Ward and Brownlee mention this as a factor in passing in their discussion of CHZs around low mass M-type stars.

To get across all of this is difficult indeed and most who do when confronted with the question about whether or not they believe there is intelligent life out there are reticent to venture an opinion.

So let us leave the experts to one side for the moment – and return to them later and consider what your typical educated lay-person – perhaps even someone with a science degree – thinks about the possible existence of aliens. Typically, although of course not always, the thought is this: the universe is so vast it is almost inevitable that we humans are not alone. A casual appreciation of astronomy introduces one to some truly vast numbers: 200 billion to 300 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy alone…and some 200 billion galaxies in the observable universe (in a universe that itself might be infinite). Such staggering numbers seem to suggest that if we were to be quite conservative and assume only 1 out of every billion stars has an Earth-like planet orbiting it where the conditions are just right, this suggests that there are 200 such planets in our galaxy alone…and 200 times 200 billion such worlds in the universe. But each week seems to bring news of more discoveries on the “exoplanet” front – we learn about super-Earths and planets in their host star’s “habitable zones”. It seems to be only a matter of time before we are going to actually see some alien craft in orbit around an alien world. These supposedly huge numbers of habitable worlds make it seem inevitable that once life gets going on a world, intelligent critters will arise as well…just as they did here on Earth. If you hope one day that aliens will be found, then this straightforward analysis makes things seem rather promising, doesn’t it?

It doesn’t – because there is a huge flaw in the argument. And it has nothing to do with astronomy and everything to do with biology.

Why, so far, has the “Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence” (SETI) so far found nothing? Here is one obvious answer: because there is nothing to find. Their aim is to find intelligent life in the universe – but of course what that really means is life capable of transmitting radio signals of the sort SETI is able to detect. But SETI can go on forever searching even if it finds nothing because it seems to be testing a hypothesis that is not falsifiable. The hypothesis “There exist intelligent aliens” is not falsifiable. It belongs to that class of statements that all religions share: “X exists”, all of which are not falsifiable. No experimental test can ever demonstrate that aliens do not exist because no search could ever be exhaustive. This being the case, the argument against the idea that there are intelligent aliens out there can never consist of direct evidence, not strictly because such evidence is lacking but rather no conceivable observation could ever be made which would constitute evidence of that sort.

But this does not mean the search has no merit. It does. The science of what to look for and how to look for it and where help propel science forward on many fronts. And the hypothesis “There exist no intelligent aliens capable of transmitting radio signals” is scientific and anyone who suggests that hypothesis is correct can be shown to be wrong by observation.

There have been many books written about the likihood of intelligent life elsewhere that we might be able to detect. Popular culture in the form of just about every science fiction book or movie ever created reinforces the idea that the galaxy might be teeming with aliens. But what about the other side of the argument? The sceptical, scientific side? One view is ventured by planetary scientists Ward and Brownlee in their volume “Rare Earth” which lays out the observations which, taken together constitutes a refutation of the popular conception of alien intelligence being ‘out there’. These refutations are collectively the basis of the position which argues that conditions required for intelligent life to arise are likely going to resemble those found on Earth, and places like Earth in the universe are likely very uncommon. This, the “Rare Earth Hypothesis” and anyone who wants to participate in an informed discussion about the possibility of intelligent life out there beyond the Solar system would do well to be familiar with at least some of these points.

Rare Earth Factors

Ward and Brownlee present a list of fortuitous circumstances that have led to the evolution of intelligent life here on Earth. It is this list that attempts to chip away at that amazingly promising billions of possible Earth-like planets that are supposedly “out there” upon which life and intelligence might arise. Ward and Brownlee present the case that life is likely going to be common in the universe and at first glance this would seem to run counter to their entire position. However, as others wish to suggest also – the appearance of microbial life indicates little about the chances of finding complex life. The conditions under which simple life can flourish we shall see are wide ranging. However, our knowledge of more complex biology suggests that animal life (especially) of sufficient sophistication that it can build a radio telescope can only survive in a far more narrow range of habitats. And importantly, there must be selection pressures which coerce evolution into following a path towards increasing complexity – but evolution must not be frustrated by geological or astrophysical events. So it is that Ward and Brownlee consider how distance from the sun and centre of the galaxy (habitable zones), extinction events – from asteroid impacts, to ice-ages and supernovae, plate tectonics (a central theme of the book) and the peculiar characteristics of this solar system (a Jupiter sized-planet and a large moon around the Earth) all come together to provide all-but-necessary if not sufficient conditions for life to begin, evolve and flourish over the billions of years it takes to permit natural selection to spit out something that is able to begin comprehending the whole she-bang.

The Rare Earth Factors (p. xxxi of Rare Earth) suggest that there is something fundamentally flawed about the argument presented in the first part of my introduction. The Rare Earth Hypothesis attempts to solve physicist Enrico Fermi’s paradox about aliens: If they are as common as that argument suggests, where are they? (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004). Indeed, per Fermi, if there is intelligent life in the universe then it would be utterly fantastic to assume that it has evolved at precisely the same time as intelligence here on Earth and so, if it can be detected by a SETI-type program then it is likely to be far more advanced – millions or perhaps even billions – of years ahead of us. And if that is the case, then it should have colonised the entire galaxy and it should be a trivial matter to detect because of its ubiquity (in much the same way as life here on Earth is so easy to detect because evidence of it is everywhere). However, we have not detected alien life, therefore it cannot be that common and so it cannot be millions of years “ahead” of us. Of course this itself may explain the null result in that a civilisation which is that far ahead of ours might “have no more interest in communicating with us than we have in talking to bacteria.” (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004 – p 299). This is a common objection to which I venture the rejoinder that we humans do try to communicate with “lower” forms of life routinely: be they other primates (whom we even teach sign language to) or whales (where we try to understand their songs) or even our pets whom we teach to obey our commands. Indeed the relationship between humans and other life forms seems to be that where we can develop a method of communication, we pursue it. Our inability to “communicate” with bacteria is less to do with our unwillingness to try as our taking seriously our theories about bacteria and what the word “communication” means. It might well be argued that antibiotics are very much an attempt to communicate a message: if you are a parasitic bacteria: stay out of human beings. Hence, I think that the analogy about aliens not wishing to communicate with us is because it would be somehow like us wanting to communicate with bacteria is false.

Some commentators to be discussed later – importantly Lineweaver – seem to suggest that Fermi’s paradox is answered by appealing not so much to physical, chemical and geological factors as to evolutionary ones. Indeed when talking large numbers, “biological” is a prefix that should indicate quantities that are greater than any described as “astronomical”. The “200 billion” (plus!) stars in the Milky Way, multiplied by the “200 billion” or so galaxies in the universe may seem “astronomical” but when one considers the chance evolutionary occurrences that have led to intelligence here on Earth…that number simply is no where near big enough to do the job of guaranteeing that ET is out there somewhere listening for our radio signals. Importantly, Lineweaver has some important observational data on his side when it comes to assessing the likelihood of intelligence elsewhere in the universe. However, prior to considering the chances of intelligent life, let us first consider some of the conditions thought necessary for any life at all to arise. We will begin with a discussion of places in the universe where biogenesis is able to occur.

Habitable Zones

The notion of a habitable zone turns in large part upon the restrictions one places upon the requirements for life. The more we learn about life, the more we seem to broaden the possibilities for locations which are “friendly” towards life. Ward and Brownlee devote Chapters 2 and 3 of their book to a discussion of habitable zones, so in this section I will briefly distinguish between circumstellar habitable zones (CHZ)* and galactic habitable zones (GHZ) and finally explain how the habitable zones for simple life – especially so-called extremophiles might be far broader than normally assumed while the habitable zones for “intelligent” complex creatures capable of interstellar communication and/or travel are likely to be far more narrow. As well as zones habitable in certain regions of space there may also only be some zones habitable in time.

*Ward and Brownlee use “CHZ” to refer to the “Continuously Habitable Zone” – that zone around a star in which a planet’s water will not, over a reasonably long period of time, boil away. For reasons of simplicity, my “CHZ” implies “continuously” as part of the definition of “Circumstellar Habitable Zone” as explained in the next section

The Circumstellar Habitable Zone (CHZ)

This is often the first point of entry for discussions about how much rarer Earth may be than is commonly thought. One of the most important factors in finding complex life in the universe is likely to be whether or not liquid water is present on the surface of a planet. For a number of reasons, liquid water seems to be the best solvent for the chemistry of life to occur in. Whatever the solvent is going to be, it should be both simple and common – water being 2-parts the most common element in the universe by any measure and 1 part oxygen (the third most abundant element in the universe, by mass, after helium) satisfies both of these criteria. Fortuitously, this chemical is a liquid over a range of temperatures unrivalled by almost any other: 100K. This is far broader than other “competitors” such as ammonia and (say) methane (45K and 22K respectively). Only ethane, which is a liquid over 95K, comes close – but it is both more complex, non-polar and with a very low boiling point. Boiling point is, of course, an important consideration for reaction rate is proportional to temperature reaction and so determines how quickly (or otherwise) the production of the requisite chemicals (such as protein synthesis and replication) and evolution occurs. Reactions in non-polar substances like ethane or methane take place over time frames that are orders of magnitude greater than the time taken for similar reactions to occur in an aqueous medium – if they can even occur at all. Water’s boiling point is far higher even than comparable hydrogen-bonded solvents such as ammonia. For these reasons and many others (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004, provide a comprehensive discussion), liquid water seems to be a prerequisite for complex life. As such, any planet on which we look for life must not be so close to its home star that all possible oceans, lakes and ponds are boiled away nor so distant that it is frozen solid to the core.

The CHZ is thus defined as being the range of distances from a star “for which liquid water can exist on a planetary surface” (Gilmour & Sephton, 2004). Importantly, the habitable zone moves as a star ages. Indeed, it will in general move away from a star as, over time, a star’s luminosity increases. This means that an important restriction upon whether or not a planet may harbour complex life that requires liquid water is to consider whether the planet is not simply within the CHZ at some given time, but rather that it is in what is referred to as the “continuous” CHZ; that is, the region around a star where liquid water could persist on the surface for some very large portion of time – likely billions of years if the evolution of life on Earth is any benchmark. For many stars this continuous CHZ is going to be narrow indeed due to the fact that many stars have shorter lifetimes than the sun.

Many stars (approximately half) exist in binary systems. It is likely to be the case that planets in orbit around binary stars are going to suffer severe perturbations, at times, of their motions. This could mean they spiral into their host stars, be flung into outer space or simply drift out of the CHZ. For all of these reasons, this entry point into discussions about how rare Earth is likely to be must necessarily begin with an acknowledgement that this most basic assumption: the fact that the Earth is in an almost perfect Goldilocks-zone around the sun is a situation that is going to be rare indeed.

Against the Rare Earth Hypothesis, some more promising arguments may be found with regards to the “narrowness” of CHZs when considering Red Dwarf stars in particular. Guinan & Engle (2009) suggest that because Red Dwarfs have a lifetime of some 50 GYrs, then even given that the CHZ is within the range of 0.05AU – 0.4AU of the host, the chance of finding conditions favourable to a long and rather tranquil stretch of time in which life can arise around such a star might be quite high indeed. Because Red Dwarf stars are by far the most numerous in the galaxy, any assessment of the constraints considerations of the CHZ place upon chances for finding life, complex or otherwise, outside the solar system, must include some analysis of the conditions which exist in the CHZs around Red Dwarfs. Guinan & Engle answer the most obvious question an astrobiologist would have about habitability of planets around such stars: if they are in the habitable zone, then would they not be tidally locked? They would be, grant Guinan and Engle, however “a thick enough atmosphere (P > 0.1 bar) is capable of transferring heat from the star-lit side of the planet to the dark hemisphere, preventing atmospheric collapse and possibly moderating the global climate.” Ward and Brownlee mention this as a factor in passing in their discussion of CHZs around low mass M-type stars.

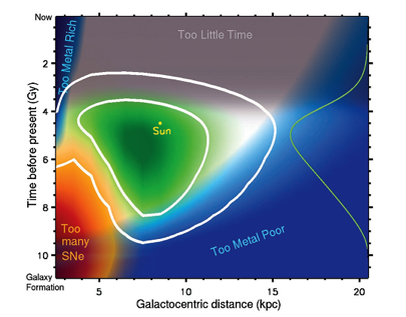

The figure above can be interpreted as suggesting that down at the bottom right of the chart (representing the inner galaxy over 6 billion years ago), Supernovae would have frustrated the appearance or evolution of life on any planets around stars in the region around the centre of the galaxy of radius 5 kpc or so. But also, it shows that there was nowhere in the galaxy for the first 3 billion years that had sufficient metals (i.e: in the idiosyncratic way astronomers refer to atoms heavier than Helium - including carbon) for life to even form with. The green region, given only a few broad assumptions is rather narrow therefore in both time and space.

Our concept of habitable zones in time and space may come together at some point in the future given the emergence of technology. What presently is an uninhabitable place in the universe may become habitable given intelligent control of the environment. Human beings can already take their water, oxygen and other life support with them to make places like “outer space” essentially habitable (at least for brief periods). Quantum Physicist David Deutsch points out that, in the limit, the entire universe really is already habitable: the real problem now is simply knowledge, not resources. Given a certain volume of intergalactic space, there is sufficient matter to construct the requisite technology and fuel to power that technology to enable human beings to survive (Deutsch, 2005). The point of this is to suggest that, again, a civilisation ahead of our own in terms of its technology could easily make the uninhabitable, habitable. Resources are not what prevent life from flourishing anywhere in the universe (for they are plentiful, says Deutsch), it is simply knowing how to collect the hydrogen in intergalactic space, fuse it together into other elements and create a space station. If that is what you needed to do, then the only thing preventing you from doing so is knowledge.

Now given that a star is in a galaxy of high average metallicity, and within a zone around the centre of that galaxy where that metallicity is high enough to form rocky planets and those planets are not so close to the centre of a galaxy that neighbouring stars pose a risk in the form of surface sterilising supernovae, then what other conditions must the planet satisfy for life to flourish upon or within it?

Plate Tectonics

A planet within both the GHZ and CHZ may nonetheless lack a climate favourable to life if the atmosphere is not just right. The atmosphere must be able to retain heat sufficient to keep the temperature within the freezing and boiling points of water. If the atmosphere were too thin and the night too long, the oceans would freeze or if the atmosphere were too thick because greenhouse gases were too concentrated then the temperature might rise beyond 100°C and the oceans would be lost. So it is that one of the most important features of the Rare Earth Hypothesis as argued by Ward and Brownlee is that the prevalence of life in the universe has much to do with just how common plate tectonics is on other planets. To this issue, they devote Chapter 9 of their book.

If a potential Earth-like planet has a rigid crust where there are no continental plates and thus no fault lines along which volcanoes can form and where eruptions of the interior can occur, then a replica of the natural thermostat that is on Earth will not be present. A reason why the Earth is able to remain temperate over time is because of the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This greenhouse gas acts as a temperature regulator. If the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is high then, due to the ability of CO2 to absorb huge amounts of heat – the global average temperature will rise. If the global average temperature rises then the sea level temperature rises. When this rises, the rate of evaporation of the oceans increases and so the humidity of the atmosphere increases and the rainfall goes up. Over time, the passage of H2O through the atmosphere as rain acts to dissolve out the CO2, creating carbonic acid (H2CO3). This carbonic acid falls onto the land and into the oceans where ultimately it forms carbonate salts – primarily calcium carbonate (limestone: CaCO3). The carbon dioxide thus removed from the atmosphere allows the overall global temperature to reduce once more and the amount of precipitation worldwide will fall. The globe cools. Plate Tectonics, however, ensure that these carbonate salts locked in rocks will be carried over time towards subduction zones between continental plates. At the subduction zones, the carbonates are liquefied once more into magma and become part of the mantle. Eventually…when a significant amount of new carbonate containing rocks have been melted and incorporated into the material below the crust, subsequent volcanic eruptions will be enriched with CO2 as carbonate rocks quickly decompose from CaCO3 (for example) back into CaO and CO2.

Without plate tectonics, the temperature of a planet will either fall or rise without limit. We see evidence of this on both Venus and Mars where plate tectonics have ceased. In our solar system, as far as we can tell, Earth is the only planet with plate tectonics. It thus seems both integral to ensuring an hospitable environment and it also seems rare so Ward and Brownlee are right to include this as part of their argument about a Rare Earth. Or are they?

A recent study throws new theoretical light upon the chances of other rocky-planets having plate tectonics. Valencia et. al (2007) discuss the geophysics of plate tectonics on super-Earths. It appears that if a planet is rocky like the Earth (at the time of the Valencia study, some 5 such planets each less than 10 times the mass of the Earth had been discovered) then its mass will determine the extent to which it experiences plate tectonics. This means for rocky planets larger than Earth – the amount of plate tectonics actually goes up. They conclude that “as planetary mass increases, the shear stress available to overcome resistance to plate motion increases while the plate thickness decreases, thereby enhancing plate weakness. These effects contribute favourably to the subduction of the lithosphere, an essential component of plate tectonics.” And so it is that where Ward and Brownlee make an excellent case for the importance of plate tectonics, Valencia et. al. demonstrate that this mechanism for maintaining a constant climate on a planet may not be all that rare at all.

So if we assume that plate tectonics is common, and with the ever increasing successes of extrasolar planet surveys revealing that not only are planets common around stars, but even rocky planets are common – we seem to be at a point where we may be able to assert that our discussion until now provides much hope for those who would like to believe that alien life is out there. It seems conditions are favourable. But how easy is it for life to arise?

The chances of life

A number of gaps still exist in our knowledge about how inanimate matter in the form of basic organic and inorganic chemicals such as water, ammonia, carbon dioxide and methane can, over time, follow some chemical pathway which leads to complex molecules which are able to make copies of themselves and thus begin the process of passing on information. In short, we are not yet sure how it is that non-living chemistry can give rise to life.

The most famous attempt at trying to replicate the conditions that prevailed on the early Earth before there was any life is known as the Miller-Urey experiment. Both high school biology students and university astrobiologists discuss the merits of taking some selection of inanimate chemicals, placing them into a flask with water, capping the mixture and then adding energy in the form of heat and electricity to see what pops out the other side after some time period. The first attempt at this type of experiment was trialled in the early 1950s by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey. They allowed warm water vapour to pass through a mixture of hydrogen, ammonia and methane in which electrodes created sparks simulating lightning. What they discovered in the collection-trap after a week were amino acids – the building blocks of life.

At first this discovery was greeted with surprise and excitement – and the importance of this discovery can perhaps not be understated. However the emphasis must be placed in the right area. What it suggests is that amino acids require little more for their creation than to throw energy at ammonia, water and methane in high enough concentrations. Indeed what we now know is that even if all of these things are actually quite low: concentration and energy – amino acids can still form spontaneously for we detect them not only in our asteroids but also in interstellar space!

Yet, the Miller-Urey experiment is often cited as evidence that life will therefore arise easily and wherever it can. Paul Davies in “The Mind of God” suggests that this way of arguing is like walking down a path, seeing a pile of dirt then a little distance later, finding a pile of rocks and assuming upon the basis of these two observations that around the next bend you will find a palace.

Repeated attempts to refine the Miller-Urey experiment using conditions we believe were closer to the conditions under which the first life forms actually arose on Earth have all failed to produce much more than simple organic chemicals. It seems that whatever is required for inorganic chemistry to eventually become chemistry that can encode information, will require more than simply throwing energy at amino acids.

This analysis seems to suggest that life is difficult to form. Yet, against this stands another observation that has been known for some time: life began as soon as it possibly could on Earth. Once the Earth cooled after its initial formation and the impacts of planet-sterilizing asteroid impacts ceased…it seems life right away began. Lineweaver & Davis (2002) adequately present and synthesize this argument in a statistical way. They state that even making the highly conservative assumption that life took 1 billion years to begin on Earth after the “Late Heavy Bombardment” ended (it actually probably only took 200 million years), then this observation means that biogenesis probably has occurred on similar terrestrial planets which are older than 1 billion years more than 36% of the time. And this figure is at the 95% confidence level. Lineweaver and Davis thus help to quantify the part of Ward and Brownlee’s Rare Earth Hypothesis: life, in the form of microbial life at least, may well be common in the universe.

So now we have come this far. The conditions in the universe might be as favourable as we can hope for life to arise – the chemicals are abundant and locations seem plentiful. We may even be able to assert that given the fact life arose on Earth as soon as it was possibly able to, then it might do the same elsewhere. So why assert, then, that the Earth is rare at all? Is Ward and Brownlee’s thesis beginning to falter? It might seem that Earth-type planets are in fact not that rare. Rocky planets with tectonic plates might be a common feature within the habitable zones of stars containing Jupiter-sized planets which are able to vacuum up hazardous comets and meteors. Yet there remains one important factor left to consider: the chance that life, once it has arisen, will evolve into something intelligent.

The Planet of the Apes Hypothesis

The scientific organisation who would have cause to argue strongly against the Rare Earth Hypothesis is SETI. Motivated by the economic imperative, they must surely bring to the fore the most powerful arguments on the side of the “principle of mediocrity” and how likely it is that not simply life, but intelligent life is (if not common) then out there somewhere. The principle of mediocrity asserts that theree is nothing particularly special about Earth as far as a place in the universe goes and, by extension therefore, whatever is here on Earth could probably be found elsewhere. From the SETI website, in answer to the FAQ “Why do we think that life is "out there"? the SETI scientists say that “…one should keep in mind that we are only one planet around a very ordinary star. There are roughly 400 billion other stars in our Galaxy, and nearly 100 billion other galaxies. It would be extraordinary if we were the only thinking beings in all these enormous realms.” The shift between talking about the (high) chances of life being prevalent in the universe to the chances of there being “thinking beings” is made swiftly and subtly and the educated lay-person may not notice it. What may be “extraordinary” is that a scientific institute would not bring a particularly scientific argument to bear on a question that surely deserves the best in science. Rather, this answer, the best they have to offer, is little more than an appeal to emotion: in this case, appeal to the emotion of “awe”: be amazed at how big the universe is and conclude on the basis of this amazement that it would be even more amazing if we alone were the only creatures capable of constructing radio telescopes.

That life, once it has arisen on a planet, will over time evolve into increasingly more complex forms, is a pervasive assumption. More than this, the idea that life, given enough time, will actually evolve something akin to human-like intelligence is a hypothesis that underlies the bulk of science fiction entertainment and even science-fact research programs like SETI. This hypothesis goes hand-in-hand with the Rare Earth Hypothesis and has been given the memorable title “The Planet of the Apes Hypothesis” (Lineweaver, 2008) which I hereafter refer to as POTAH.

POTAH is named after that film of 1968 (and later television series) where the underlying premise is that after a nuclear war in which human civilisation is wiped out, other great apes rise up to fill the vacated intelligence “niche” in the environment. So it is, therefore, in the movie that chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas learn to farm, speak English and essentially behave for all intents and purposes like the human beings they have replaced. In biological terms, what this film asserts is that intelligence is a convergent feature of evolution. Indeed Star Trek, Star Wars and almost every science fiction work of art ever produced is predicated upon the assumption that human-like intelligence is a convergent feature of evolution.

Convergent evolution is a type of evolution, to be contrasted with “divergent” or “parallel”. In convergent evolution, clades whose common ancestors lack a particular feature, independently evolve some similar feature. The classic example is that of the wing: bats, birds and insects all evolved from a creature unable to fly. Independently each of these organisms developed the ability to fly. It is whether or not human-like intelligence fits this type of evolution or not that the POTAH turns on. And, importantly, would essentially decide just how rare Earth is.

Lineweaver begins his book chapter in the reference cited with an anecdote about how he once taught a course called “Are we alone?” at the University of New South Wales where one of the lectures involved 6 or so experts from various backgrounds discussing their opinions of the values of the various numbers in the Drake Equation. As I was actually a student in this very course, with Lineweaver as lecturer, I can attest that our recollection of the debate is essentially the same. The least contentious terms were the first ones in the Drake Equation: the number of stars in the Milky Way and the number of stars with Earth-like planets. However the term that generated the most debate seems to be: once an Earth-like planet has life, what fraction of those go on to have human-like intelligence evolve on them? As per Sagan, astronomers define human-like intelligence as that able to build a radio telescope. The reason for this is because if an otherwise intelligent creature cannot (at a minimum) build a radio telescope, then we have no way of ever detecting them and for all intents and purposes they may as well not be “out there”. In this author’s opinion, in order to avoid long and tedious debates with non-astronomers on this very topic, it is sometimes more useful to simply refer to the figure provided by the Drake Equation as “that number of planets in the galaxy where life has developed the capacity to communicate over interstellar distances and this be detectable” and so avoid the emotive term “intelligence”. However, for the purpose of this project, I too shall agree to use Sagan’s definition.

What we wish to discover is whether or not this feature of life here on Earth, seemingly possessed only in a sufficiently great quantity by homo sapiens, that we have termed intelligence, could have arisen elsewhere in the universe. We would expect that if there is life elsewhere in the universe then it will acquire some of the same characteristics that life here on Earth has acquired: indeed those that are arguing that there is intelligent life out there beyond Earth are doing exactly this: they are arguing that a certain characteristic of life here on Earth: namely that of intelligence, is likely to be possessed by extra-terrestrial life. What we should be able to say at a minimum is that if there is life beyond the Earth and if that life obeys that law of biology that we have discovered here on Earth; namely that life evolves according to evolution by natural selection of random mutations, then surely we should find in that life evidence of convergent evolution. Given this – if we find complex life beyond Earth then that complex life should independently evolve some of the convergent features of evolution that life here on Earth has evolved: like wings, bipedalism and multicellularity.

Although Lineweaver does not mention it, biophysicist Joe Wolfe of The University of New South Wales first prompted during the Drake Equation Lecture that the experiment as to whether intelligence is a convergent feature of evolution or not has already been done here on Earth. In fact that experiment has been done on Earth and repeated 6 times. The experiments have been now called Africa, Australia, New Zealand, South America, Madagascar, India and North America.

The argument by Wolfe and expanded upon by Lineweaver essentially runs thus:

We can consider certain attributes of organisms a “niche”. So for example, grazing is a niche that is filled in Africa by zebra, gazelle and countless other large animals, the same niche is filled in Australia by Kangaroos and in North America by Buffalo while the burrowing niche is filled by Meercats in Africa, Tasmanian Devils in Australia and Hedgehogs in North America. So what about intelligence? Is it a niche?

50 million years ago, the continents looked roughly as they do now. Certainly, they were separate. On Africa, we set the experiment running for some 5 million years after the common ancestor of Humans and Gorillas split into those two families and we note that homo sapiens evolve. Left alone, for well over 50 million years (it can be argued that the continents were essentially separate up to 200 million years ago) we find that in Australia the most complex organisms that evolved were koalas, on Madagascar we have Lemurs, in South America and India we have Monkeys and in the Oceans we have dolphins. Wolfe’s point is to ask “how much longer than around 200 million years are we expected to wait for complex animals to evolve the capacity to be able to communicate across interstellar distances?” If human beings did not evolve in Africa, how long would one need to leave all the life on Australia alone for any of the species currently inhabiting that continent to evolve something akin to human-like intelligence? The question is not meant to be rhetorical. There is evidence that it is answerable as given the countless millions of species extant and extinct we know that only one of them ever developed human-like intelligence. This surely is an indication that human-like intelligence is anything but convergent feature of evolution. Given the experiments of the separate continents here on Earth, we find that life seems not to find the characteristic of intelligence as useful an attribute for survival as, say, wings or bipedalism which again and again evolved independently.

Lineweaver quotes Frank Drake himself as stating that the reason he, like many people believe that the SETI project is a worthwhile venture likely to yield results is that if you look at the fossil record, what you find is evidence of increasing complexity. Importantly, what you find is that the relative size of the brain over time increases.

Philosopher Peter Slezak, suggested in the panel discussion at UNSW for us to consider the number of independent, but necessary mutations that were selected for in the chain of evolution that led from simple bacteria to human-like intelligence. It seems that if there were many evolutionary paths to human-like intelligence (such as there are with wings) then the odds would be lower – but as far as we can tell, there seems to be a single evolutionary path that works – namely the path that has led to us. Such a path contains millions of steps. But let us be ridiculously conservative and assume that only 100 such steps are required. Now further, each of those independent, but necessary steps had a certain probability of occurring. Possibly the probability of each step was 1/100 or less. Let us be conservative and assume each step had a ½ chance of occurring (Slezak actually uses the figure of 1/10 – but I am being even more conservative than he). Now if each step has a ½ chance and there are 100 such steps, this means that the probability of replicating that chain of events required to reach an organism with intelligence is going to be (1/2)^100 = 7.9 x 10^-31. This number is difficult to appreciate – but essentially suggests that even if all the Earth like planets in the universe were covered in bacteria, the chance of finding another sample of intelligent life would still be essentially zero. In other words, no matter how astronomical the number of stars and planets in the universe may be, the biological odds of recreating some evolutionary pathway to intelligence is so small as to blow the astronomical number out of the water.

Carl Sagan however believed that the number of independent pathways towards intelligence are likely to be not simply more than just one, but numerous. (Sagan, 1995). It would seem however, that unless the number of pathways to intelligence is absolutely staggering then it is unlikely to make much of a dent in the number calculated above which it must be emphasized is ridiculously conservative – and, given the evidence we have been looking at life on Earth and in the fossil record, is the best model we have for the probability of life arising. In other words, as far as we can tell, given the best evidence on hand, intelligence has only one way of evolving: namely that leading to homo sapiens.

Lineweaver goes to some length to explain why it is that arguing there is a trend towards increasing “complexity” or “intelligence” in the fossil record is flawed. He points out that starting from any sufficiently extreme feature and working back will always seem to indicate a trend towards that feature. A common asserted phenomena here is what is referred to as “increasing encephalisation quotient or EQ”. EQ is a measurement of the size of the brain cavity compared to body mass. It appears that looking back through the fossil record, EQ increases. So it seems that evolution is selecting for greater and greater relative brain sizes and therefore intelligence. However Lineweaver asks us to consider what would happen if we were not humans but elephants in which case we would be more interested in what he calls the the “nasalation quotient” which the fossil record shows there has been a gradual trend of increase in. All of the ancestors of modern elephants had shorter trunks, showing a trend in evolution towards towards long trunks. The point is that the trend towards longer noses is not a trend at all. We can see that easily for our trunks are no longer than those of our ancestors. The “trend” of long noses in elephants is not a general trend that occurs across species and certainly cannot be regarded as a convergent feature of evolution. Similarly human like intelligence cannot be convergent despite the insistence that there seems to be a trend.

Intelligence is a wispy term and astronomers and astrobiologists are careful to use the word in a very restricted sense: that being the sense originally suggested by Sagan: the ability to create a radio telescope. As such when a paper such as that published in Science in 2004 titled “The Mentality of Crows: Convergent Evolution of Intelligence in Corvids and Apes” (Emery & Clayton, 2004) and we see it argued that intelligence has indeed evolved independently in species whose last common ancestor was certainly not intelligent we must notice that the word “intelligent” here is far removed from anything to do with radio telescopes.

Conclusions

The Earth which is rare in “The Rare Earth Hypothesis” is an ambiguous planet. On the one hand it seems, according to Ward and Brownlee that the very conditions that permitted life to arise and flourish on this Earth may have been so fortuitous as to be unlikely elsewhere. Yet as we have seen, the potential for a planet to form in a GHZ and exist in a CHZ is probably quite good. Moreover, recent studies even suggest that what was hitherto believed to be a very rare characteristic of Earth based upon our observations of this solar system – namely the chance of there being plate tectonics – is not rare at all. Indeed if a planet is more massive than Earth, but still rocky, it might even have more plate tectonics. And this might be a good thing, as even older terrestrial planets would then have more time for life to arise.

However, if we consider Earth to be that planet upon which intelligence has arisen, then it may be a rare thing indeed. The chances of finding another Earth in this sense then have less to do with the astrophysical, geophysical and chemical conditions (which all might be favourable) but rather the biological laws that govern evolution. If our theory of natural selection is correct, our observations show that intelligence is simply not a convergent feature of evolution. We know this from our observation of the evolution of life over billions of years here on Earth. That we are here at all to assess the odds seems a vanishingly small chance occurrence. That we are the only beings in the universe able to assess those odds, we do not know. But what we do know about those odds, seems to indicate that we are a very rare creature on a Rare Earth.

A few references including links to some useful papers:

Davies, P. “The Mind of God”. Penguin, (1996)

Deutsch, D “Our place in the Cosmos” TED; Ideas worth Spreading Video (2005), available at http://www.ted.com/index.php/talks/david_deutsch_on_our_place_in_the_cosmos.html

Emery N., and Clayton, N. “The Mentality of Crows: Convergent Evolution of Intelligence in Corvids and Apes” Science 10 December 2004: Vol. 306. no. 5703, pp. 1903 – 1907 Gilmour, I., & Sephton, M. “An introduction to Astrobiology” Cambridge University Press (2004).

Kashefi, K. & Lovley, D. “Extending the Upper Temperature Limit for Life” Science 15 August 2003: 934 Lineweaver, C.H., Davis, T., “What can rapid terrestrial biogenesis tell us about life in the universe?” Bioastronomy, 2002 “Life among the stars” Conference Proceedings. Preprint available at http://www.mso.anu.edu.au/~charley/papers/HamiltonProb.pdf

Lineweaver, C. H, Fenner, Y., Gibson, B., “The Galactic Habitable Zone and the Age Distribution of Complex Life in the Milky Way.” Science, Vol. 303 (2004).

Lineweaver C.H., 2009, in "From Fossils to Astrobiology", edt. J. Seckbach & M. Walsh Vol 13 of a series on Cellular Origins and Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology “Paleontological Tests: Human-like Intelligence is not a Convergent Feature of Evolution”, Springer, pp 353-368 available at http://www.mso.anu.edu.au/~charley/papers/ConvergenceIntelligence10.pdf

Pranztos, N. (2006) “On the Galactic Habitable Zone” Strategies for Life Detection, ISSI Bern, April 24-28 2006 Available at arXiv:astro-ph/0612316

Sagan, C. (1995) The Abundance of Life-Bearing Planets. Bioastron. News 7(4). Available online at:

http://www.planetary.org/html/UPDATES/seti/Contact/debate/Sagan.htm.

Valencia, D., O'Connell, R., & Sasselov D. “Inevitability of Plate Tectonics on Super-Earths” The Astrophysical Journal, volume 670, part 2 (2007) Pre-print at http://lanl.arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/0710/0710.0699v1.pdf

Ward, P., Brownlee, D. “Rare Earth” Copernicus Books (2004).

Our concept of habitable zones in time and space may come together at some point in the future given the emergence of technology. What presently is an uninhabitable place in the universe may become habitable given intelligent control of the environment. Human beings can already take their water, oxygen and other life support with them to make places like “outer space” essentially habitable (at least for brief periods). Quantum Physicist David Deutsch points out that, in the limit, the entire universe really is already habitable: the real problem now is simply knowledge, not resources. Given a certain volume of intergalactic space, there is sufficient matter to construct the requisite technology and fuel to power that technology to enable human beings to survive (Deutsch, 2005). The point of this is to suggest that, again, a civilisation ahead of our own in terms of its technology could easily make the uninhabitable, habitable. Resources are not what prevent life from flourishing anywhere in the universe (for they are plentiful, says Deutsch), it is simply knowing how to collect the hydrogen in intergalactic space, fuse it together into other elements and create a space station. If that is what you needed to do, then the only thing preventing you from doing so is knowledge.

Now given that a star is in a galaxy of high average metallicity, and within a zone around the centre of that galaxy where that metallicity is high enough to form rocky planets and those planets are not so close to the centre of a galaxy that neighbouring stars pose a risk in the form of surface sterilising supernovae, then what other conditions must the planet satisfy for life to flourish upon or within it?

Plate Tectonics

A planet within both the GHZ and CHZ may nonetheless lack a climate favourable to life if the atmosphere is not just right. The atmosphere must be able to retain heat sufficient to keep the temperature within the freezing and boiling points of water. If the atmosphere were too thin and the night too long, the oceans would freeze or if the atmosphere were too thick because greenhouse gases were too concentrated then the temperature might rise beyond 100°C and the oceans would be lost. So it is that one of the most important features of the Rare Earth Hypothesis as argued by Ward and Brownlee is that the prevalence of life in the universe has much to do with just how common plate tectonics is on other planets. To this issue, they devote Chapter 9 of their book.

If a potential Earth-like planet has a rigid crust where there are no continental plates and thus no fault lines along which volcanoes can form and where eruptions of the interior can occur, then a replica of the natural thermostat that is on Earth will not be present. A reason why the Earth is able to remain temperate over time is because of the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This greenhouse gas acts as a temperature regulator. If the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is high then, due to the ability of CO2 to absorb huge amounts of heat – the global average temperature will rise. If the global average temperature rises then the sea level temperature rises. When this rises, the rate of evaporation of the oceans increases and so the humidity of the atmosphere increases and the rainfall goes up. Over time, the passage of H2O through the atmosphere as rain acts to dissolve out the CO2, creating carbonic acid (H2CO3). This carbonic acid falls onto the land and into the oceans where ultimately it forms carbonate salts – primarily calcium carbonate (limestone: CaCO3). The carbon dioxide thus removed from the atmosphere allows the overall global temperature to reduce once more and the amount of precipitation worldwide will fall. The globe cools. Plate Tectonics, however, ensure that these carbonate salts locked in rocks will be carried over time towards subduction zones between continental plates. At the subduction zones, the carbonates are liquefied once more into magma and become part of the mantle. Eventually…when a significant amount of new carbonate containing rocks have been melted and incorporated into the material below the crust, subsequent volcanic eruptions will be enriched with CO2 as carbonate rocks quickly decompose from CaCO3 (for example) back into CaO and CO2.

Without plate tectonics, the temperature of a planet will either fall or rise without limit. We see evidence of this on both Venus and Mars where plate tectonics have ceased. In our solar system, as far as we can tell, Earth is the only planet with plate tectonics. It thus seems both integral to ensuring an hospitable environment and it also seems rare so Ward and Brownlee are right to include this as part of their argument about a Rare Earth. Or are they?

A recent study throws new theoretical light upon the chances of other rocky-planets having plate tectonics. Valencia et. al (2007) discuss the geophysics of plate tectonics on super-Earths. It appears that if a planet is rocky like the Earth (at the time of the Valencia study, some 5 such planets each less than 10 times the mass of the Earth had been discovered) then its mass will determine the extent to which it experiences plate tectonics. This means for rocky planets larger than Earth – the amount of plate tectonics actually goes up. They conclude that “as planetary mass increases, the shear stress available to overcome resistance to plate motion increases while the plate thickness decreases, thereby enhancing plate weakness. These effects contribute favourably to the subduction of the lithosphere, an essential component of plate tectonics.” And so it is that where Ward and Brownlee make an excellent case for the importance of plate tectonics, Valencia et. al. demonstrate that this mechanism for maintaining a constant climate on a planet may not be all that rare at all.

So if we assume that plate tectonics is common, and with the ever increasing successes of extrasolar planet surveys revealing that not only are planets common around stars, but even rocky planets are common – we seem to be at a point where we may be able to assert that our discussion until now provides much hope for those who would like to believe that alien life is out there. It seems conditions are favourable. But how easy is it for life to arise?

The chances of life

A number of gaps still exist in our knowledge about how inanimate matter in the form of basic organic and inorganic chemicals such as water, ammonia, carbon dioxide and methane can, over time, follow some chemical pathway which leads to complex molecules which are able to make copies of themselves and thus begin the process of passing on information. In short, we are not yet sure how it is that non-living chemistry can give rise to life.

The most famous attempt at trying to replicate the conditions that prevailed on the early Earth before there was any life is known as the Miller-Urey experiment. Both high school biology students and university astrobiologists discuss the merits of taking some selection of inanimate chemicals, placing them into a flask with water, capping the mixture and then adding energy in the form of heat and electricity to see what pops out the other side after some time period. The first attempt at this type of experiment was trialled in the early 1950s by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey. They allowed warm water vapour to pass through a mixture of hydrogen, ammonia and methane in which electrodes created sparks simulating lightning. What they discovered in the collection-trap after a week were amino acids – the building blocks of life.

At first this discovery was greeted with surprise and excitement – and the importance of this discovery can perhaps not be understated. However the emphasis must be placed in the right area. What it suggests is that amino acids require little more for their creation than to throw energy at ammonia, water and methane in high enough concentrations. Indeed what we now know is that even if all of these things are actually quite low: concentration and energy – amino acids can still form spontaneously for we detect them not only in our asteroids but also in interstellar space!

Yet, the Miller-Urey experiment is often cited as evidence that life will therefore arise easily and wherever it can. Paul Davies in “The Mind of God” suggests that this way of arguing is like walking down a path, seeing a pile of dirt then a little distance later, finding a pile of rocks and assuming upon the basis of these two observations that around the next bend you will find a palace.

Repeated attempts to refine the Miller-Urey experiment using conditions we believe were closer to the conditions under which the first life forms actually arose on Earth have all failed to produce much more than simple organic chemicals. It seems that whatever is required for inorganic chemistry to eventually become chemistry that can encode information, will require more than simply throwing energy at amino acids.

This analysis seems to suggest that life is difficult to form. Yet, against this stands another observation that has been known for some time: life began as soon as it possibly could on Earth. Once the Earth cooled after its initial formation and the impacts of planet-sterilizing asteroid impacts ceased…it seems life right away began. Lineweaver & Davis (2002) adequately present and synthesize this argument in a statistical way. They state that even making the highly conservative assumption that life took 1 billion years to begin on Earth after the “Late Heavy Bombardment” ended (it actually probably only took 200 million years), then this observation means that biogenesis probably has occurred on similar terrestrial planets which are older than 1 billion years more than 36% of the time. And this figure is at the 95% confidence level. Lineweaver and Davis thus help to quantify the part of Ward and Brownlee’s Rare Earth Hypothesis: life, in the form of microbial life at least, may well be common in the universe.

So now we have come this far. The conditions in the universe might be as favourable as we can hope for life to arise – the chemicals are abundant and locations seem plentiful. We may even be able to assert that given the fact life arose on Earth as soon as it was possibly able to, then it might do the same elsewhere. So why assert, then, that the Earth is rare at all? Is Ward and Brownlee’s thesis beginning to falter? It might seem that Earth-type planets are in fact not that rare. Rocky planets with tectonic plates might be a common feature within the habitable zones of stars containing Jupiter-sized planets which are able to vacuum up hazardous comets and meteors. Yet there remains one important factor left to consider: the chance that life, once it has arisen, will evolve into something intelligent.

The Planet of the Apes Hypothesis

The scientific organisation who would have cause to argue strongly against the Rare Earth Hypothesis is SETI. Motivated by the economic imperative, they must surely bring to the fore the most powerful arguments on the side of the “principle of mediocrity” and how likely it is that not simply life, but intelligent life is (if not common) then out there somewhere. The principle of mediocrity asserts that theree is nothing particularly special about Earth as far as a place in the universe goes and, by extension therefore, whatever is here on Earth could probably be found elsewhere. From the SETI website, in answer to the FAQ “Why do we think that life is "out there"? the SETI scientists say that “…one should keep in mind that we are only one planet around a very ordinary star. There are roughly 400 billion other stars in our Galaxy, and nearly 100 billion other galaxies. It would be extraordinary if we were the only thinking beings in all these enormous realms.” The shift between talking about the (high) chances of life being prevalent in the universe to the chances of there being “thinking beings” is made swiftly and subtly and the educated lay-person may not notice it. What may be “extraordinary” is that a scientific institute would not bring a particularly scientific argument to bear on a question that surely deserves the best in science. Rather, this answer, the best they have to offer, is little more than an appeal to emotion: in this case, appeal to the emotion of “awe”: be amazed at how big the universe is and conclude on the basis of this amazement that it would be even more amazing if we alone were the only creatures capable of constructing radio telescopes.

That life, once it has arisen on a planet, will over time evolve into increasingly more complex forms, is a pervasive assumption. More than this, the idea that life, given enough time, will actually evolve something akin to human-like intelligence is a hypothesis that underlies the bulk of science fiction entertainment and even science-fact research programs like SETI. This hypothesis goes hand-in-hand with the Rare Earth Hypothesis and has been given the memorable title “The Planet of the Apes Hypothesis” (Lineweaver, 2008) which I hereafter refer to as POTAH.

POTAH is named after that film of 1968 (and later television series) where the underlying premise is that after a nuclear war in which human civilisation is wiped out, other great apes rise up to fill the vacated intelligence “niche” in the environment. So it is, therefore, in the movie that chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas learn to farm, speak English and essentially behave for all intents and purposes like the human beings they have replaced. In biological terms, what this film asserts is that intelligence is a convergent feature of evolution. Indeed Star Trek, Star Wars and almost every science fiction work of art ever produced is predicated upon the assumption that human-like intelligence is a convergent feature of evolution.

Convergent evolution is a type of evolution, to be contrasted with “divergent” or “parallel”. In convergent evolution, clades whose common ancestors lack a particular feature, independently evolve some similar feature. The classic example is that of the wing: bats, birds and insects all evolved from a creature unable to fly. Independently each of these organisms developed the ability to fly. It is whether or not human-like intelligence fits this type of evolution or not that the POTAH turns on. And, importantly, would essentially decide just how rare Earth is.

Lineweaver begins his book chapter in the reference cited with an anecdote about how he once taught a course called “Are we alone?” at the University of New South Wales where one of the lectures involved 6 or so experts from various backgrounds discussing their opinions of the values of the various numbers in the Drake Equation. As I was actually a student in this very course, with Lineweaver as lecturer, I can attest that our recollection of the debate is essentially the same. The least contentious terms were the first ones in the Drake Equation: the number of stars in the Milky Way and the number of stars with Earth-like planets. However the term that generated the most debate seems to be: once an Earth-like planet has life, what fraction of those go on to have human-like intelligence evolve on them? As per Sagan, astronomers define human-like intelligence as that able to build a radio telescope. The reason for this is because if an otherwise intelligent creature cannot (at a minimum) build a radio telescope, then we have no way of ever detecting them and for all intents and purposes they may as well not be “out there”. In this author’s opinion, in order to avoid long and tedious debates with non-astronomers on this very topic, it is sometimes more useful to simply refer to the figure provided by the Drake Equation as “that number of planets in the galaxy where life has developed the capacity to communicate over interstellar distances and this be detectable” and so avoid the emotive term “intelligence”. However, for the purpose of this project, I too shall agree to use Sagan’s definition.

What we wish to discover is whether or not this feature of life here on Earth, seemingly possessed only in a sufficiently great quantity by homo sapiens, that we have termed intelligence, could have arisen elsewhere in the universe. We would expect that if there is life elsewhere in the universe then it will acquire some of the same characteristics that life here on Earth has acquired: indeed those that are arguing that there is intelligent life out there beyond Earth are doing exactly this: they are arguing that a certain characteristic of life here on Earth: namely that of intelligence, is likely to be possessed by extra-terrestrial life. What we should be able to say at a minimum is that if there is life beyond the Earth and if that life obeys that law of biology that we have discovered here on Earth; namely that life evolves according to evolution by natural selection of random mutations, then surely we should find in that life evidence of convergent evolution. Given this – if we find complex life beyond Earth then that complex life should independently evolve some of the convergent features of evolution that life here on Earth has evolved: like wings, bipedalism and multicellularity.

Although Lineweaver does not mention it, biophysicist Joe Wolfe of The University of New South Wales first prompted during the Drake Equation Lecture that the experiment as to whether intelligence is a convergent feature of evolution or not has already been done here on Earth. In fact that experiment has been done on Earth and repeated 6 times. The experiments have been now called Africa, Australia, New Zealand, South America, Madagascar, India and North America.

The argument by Wolfe and expanded upon by Lineweaver essentially runs thus:

We can consider certain attributes of organisms a “niche”. So for example, grazing is a niche that is filled in Africa by zebra, gazelle and countless other large animals, the same niche is filled in Australia by Kangaroos and in North America by Buffalo while the burrowing niche is filled by Meercats in Africa, Tasmanian Devils in Australia and Hedgehogs in North America. So what about intelligence? Is it a niche?