|

Eric Weinstein is a very intelligent person. I'm on his side in many things (but absolutely not the top-down control he simply assumes MUST be a part of the global economy and "free" market. See here for example: https://www.edge.org/conversation/lee_smolin-stuart_a_kauffman-zoe-vonna_palmrose-mike_brown-can-science-help-solve-the#21964 (in a sense he may even have earned much fame for calling for an "economic Manhattan project". If only he meant: let's have a huge government program to get government out of the business of tinkering with economies, it'd be great. But actually? He means something more like the opposite...). Whatever the case, Eric does have lots to say and many people listen. He can't be dismissed as a postmodernist - but one could understandably make the mistake, because his use of the English language has a style that eschews clarity because of its idiosyncrasies. We all use language idiosyncratically, of course - but the desire to almost continually invent new words or usages for old ones is a strong impulse in some. Eric is simply a prominent example.

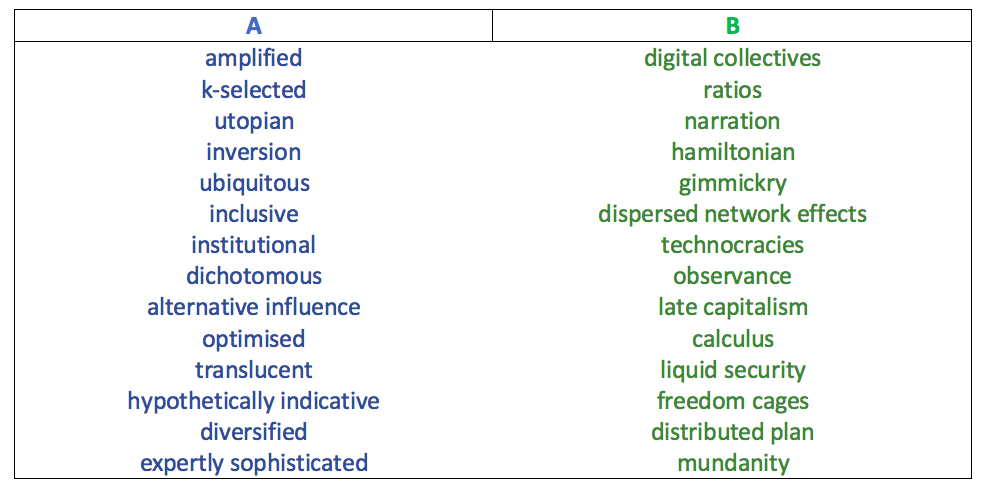

Take the talk by Eric at https://bigthink.com/videos/eric-weinstein-capitalism-is-in-trouble-socialist-principles-can-save-it (The transcript is available there). At one point he says, “Now the danger of that is that what we didn’t realize is that our technical training for occupations maneuvers the entire population into the crosshairs of software.” Translation: Everyone might lose their jobs to computers. Now aside from the fact this is flat out false (creativity, from what we know is a unique feature people have and will always be needed) it’s just expressed in such tortuous, clunky language as to muddy the meaning. Anyways that’s just one example. False philosophy shrouded in jargon. It’s not postmodernist nonsense. But it’s flirting with the style if not the substance. The whole talk, by the way, is an appeal for power and influence. He wants scientists to have more authority and bemoans the fact politicians are from “softer disciplines”. He’s upset and demands change. He says, “One of the things that I find most perplexing is that our government is still populated by people who come from sort of softer disciplines if you will. Whether that’s law, whether these people come from poli-sci, very few people in government come from a hard core technical background. There are very few senators who could solve a partial differential equation or representatives who could program a computer.” That’s clear and lacks jargon! He should stick with that style (though the substance itself this time is terrible: No thought is given to how useful those things are in creating legislation or making decisions - the task of politicians. There are probably very few Engineers or Scientists who could effectively debate, consult widely, speak clearly and publicly and simultaneously manage large groups of people. Eric himself may be one of the rare exceptions, granted. I digress: The following is meant purely as friendly fun (ok, to make a point and help out allies, perhaps). Again, Eric makes some excellent points when speaking and writing. Yet I think sometimes those points would be so much more powerful if only they were clearer. To that end, here is the beginnings of a generator for creating your own Eric-sounding neologisms. I was going to name it after him, or make fun of his name - but that seemed to cross a line. So, instead, the name of my generator commits the same sin as it perpetuates. Here's my advertisement: Do you have something insightful to say but want to cloud it in strange idiosyncratic nomenclature? Or perhaps you've no real point to make, and just feel a little "postmodern"? With the idiosyncratic neologism generator you can cloak any clear message in obtuse usage of otherwise pedestrian words. Take any term from the left hand column and pick any term on the right - it's that easy. Maybe you want to observe that sometimes people tend to waste some of their time by making silly bordering-on-mean blog posts about famous intellectuals? Need a term for that? What about...hmmm..."inversion gimmickry". And right there, you're done. Just take a pinch of column A and a random sprinkling of column B and you can spice up any vanilla concept. Turn any mundane turn of phrase into something cosmically momentous now! Testimonials "I just wanted to complain about being unable to find a date on Friday night, but didn't want to take any personal responsibility. Now I can attribute it to "ubiquitous dispersed network effects" and I feel so much better about myself!" - Terry, 19, Dubbo "I've always been a communist but because promoting those ideas is so very difficult I just complain about "amplified late capitalism" instead and people now nod judiciously! Thanks idiosyncratic neologism generator!" Jill, 52, New York "My final undergrad project counted how many times the word "man" was used in Time magazine between 1989 and 2016. But "How many times the word "man" was used in Time magazine between 1989 and 2016" as a title was rejected by my supervisor. With "Institutional hamiltonian calculus of gendered language in popular media: 1989 to 2016" I was able to get Honours First Class!" - Summer Clouds, No age, Citizen of the Universe

0 Comments

I recall watching this speech Sam Harris gave at the Aspen Ideas Festival well over a decade ago now. https://youtu.be/-j8L7p-76cU I found it amazing then and I must have watched it more than a dozen times since. I recall wanting to learn to speak like that. Even now I haven’t seen a clearer, good humoured and more forceful defence of reason against faith. There’s a strong sense in which I feel I owe Sam some gratitude for having taught me to talk. His style is an ideal to move towards: speaking clearly, with good humour and concede where concession is warranted. In that speech you can hear for yourself all the ways in which Sam’s most vociferous detractors and opponents lie about his positions and have misrepresented his motivation. And where he concedes religion can indeed be very useful and consoling and more besides.

Sam has had to defend himself many times against the charge he’s unusually or even unfairly focussed on religion. And one religion in particular. He has been absolutely right to respond that in fact this doesn’t quite get to the heart of what truly motivates him. Actually, what Sam is concerned about rather often - and this comes through in his talk and in his books - is dogma. Religion is not centre of the bullseye (even if it’s on the dart board). The central concern is dogma. It is just that religion is rather typically, one of the largest most robust repositories of dogma. And this focus on dogma exists precisely because it can cause such harm - and we often don’t realise how until the harm is or has been done. Almost always it’s unintentional. A great example Sam uses is how the Catholic Church teaches that “human life begins at the moment of conception”. This seems quaint-even sweet and good. In one sense it’s true (zygotes are alive) but on the other hand zygotes are not people. And Sam observes that if the argument is “they are potential people” then given the right conditions so is any cell in your body. So when one scratches their nose, on this view, they’re engaged in a veritable genocidal level of murder of “potential humans”. But this Catholic doctrine – this dogma is a foundational claim. It is from here that they build moral structure – they reach other conclusions about the rightness and wrongness of many other things; for example, abortion and the use of stem cells. This foundational claim about human life* beginning at conception does real harm. But the harm isn’t due primarily to the fact it’s false (and it is false - zygotes are not people - at a minimum a nervous system is needed to encode the knowledge that makes a person a person)- it’s damaging because the church will not even consider the possibility that there might be a way to learn more on this topic or to consider it different. Because it’s a foundational claim. It’s Church doctrine. A dogma. And this is why it can result in terrible suffering in ways the early church scholars could never possibly have foreseen. For in the context of a world that can treat actual suffering of actual people if only we could use embryonic stem cells, we have a problem. (Now, by the way, I don’t think it’s at all clear WHEN a zygote becomes a person. I know it’s not one. Nor would a blastocyst be one. But an embryo? Now I don’t know. This is a sorites problem of real consequence) so the moral foundation “Human life begins at the moment of conception” - good though it sounds as a way of enshrining the sanctity of life - turns out in the context of modern medical procedures - to cause real harm. Or in the case of abortion where early term abortions are made unavailable to victims of rape, the foundation would seem to be a perfect engine of suffering. So Sam is absolutely right to root out and condemn dogma. Dogma are irrational. But it’s how religions build belief systems. They build upon axiomatic claims – foundations. It is purported to be somewhat like a mathematical system. Here are the axioms: now, let’s see what follows. Of course nothing can ever show axioms are true and indeed they may be false. So what follows in such a case is liable to be false also. Some mathematicians - it must be said - can sometimes admit (in better moods) that they aren’t interested in what is actually true in reality. Rather: just what follows as a matter of logical necessity. Quite right too! (*Note: by “human life” the Catholic Church means the life of the zygote is a human. They mean: there are human souls in those zygotes. ) So Sam rejects dogma because it’s dogma. He understands that dogma are those things we cannot improve if we take seriously the idea they must be true. He’s focussed on that. And I couldn’t agree more. But what is the difference between a foundation (even a weak one) and a dogma? Moreover, what exactly follows from Sam’s axioms? Can they be the basis of some nascent all encompassing moral system of a kind? One thing we might observe is that if morality is about “the well being of conscious creatures” then this reduces morality to a domain of feelings. Indeed Sam’s other axioms: “we should avoid the worst possible misery for everyone” is explicitly about the feeling of suffering. But this *central* focus on feelings in objective matters is a mistake. It takes what should be an objective domain of enquiry (morality) and reduces it to questions of “how do you feel?” or “how do we feel?” and so on. Now very often our feelings of pain or joy are indeed relevant. But are feelings the best guide in all cases? Could we formulate moral systems without these axioms? Let us consider any other objective domain of enquiry and the relationship there between knowledge creation (i.e: the solving of problems) and the existence of “foundations” or axioms. In physics there exist postulates for various reasons. So Einstein “built” special relativity upon two postulates: the speed of light is constant for all observers and the laws of physics are the same for all observers. But this hardly helps with thermodynamics. And large parts of quantum theory were created to solve problems without being concerned about the postulates of special relativity. That’s physics. As to mathematics – well there is the preeminent example of an domain where axiomatic systems rule the day. But Gödel showed in mathematics we cannot have a complete set of axioms that can ever solve all mathematical problems. So in physics: not everything *follows from* the 2 postulates of special relativity. And in mathematics it is provably the case we cannot prove everything from any given set of axioms. So much for axiomatic systems being needed to create knowledge and solve problems. Instead of a focus on axioms, the truth is that in all cases creativity is how we find solutions. It does not happen via derivation. If this is true in mathematics and physics - that the majority of what we know *cannot be derived* from a fixed set of axioms why should we think it possible in morality? As to Sam’s two premises - I have no great criticisms against morality being concerned with the problems of conscious creatures and that we need to avoid the worst possible misery for everyone. But I’ve no criticisms against either of those or Einstein’s postulates or indeed many of the best ideas. That’s why they’re best. I just don’t ever elevate my best ideas to foundational or dogmatic nor indeed regard them as any kind of “necessary starting point”. So while I lack “coherent criticisms” of Sam’s axioms, they’re not necessary as a foundation or a starting point for any moral discussion. They’re just useful if our interlocutor tries to assert that x is better than y even when x causes lots more suffering. Or that feelings never matter at all. If indeed we tried to build a system of ethics upon them, we’d be talking about suffering and feelings constantly. We’d descend into subjective debates about subjectivity. We don’t need foundations – just claims that remain tentative. As indeed Einstein’s postulates in special relativity are. I cannot conceive how Einstein’s postulates might be true (in our actual universe). They must be, it seems to me given what else I know. Likewise “the worst possible misery for everyone is bad” is an excellent critique against those who would push a moral relativism. There is no argument I know against that claim so cannot conceive of how it might be false. But now from here what do we do? If this is the starting point, where then? Do we move left or right, north or south away from the worst possible misery? While we agree we must move – is it a coin toss? If not what should we do? That’s the real moral question that the foundation simply cannot help with. Sam’s foundational claims may seem unproblematic. But then so too did the claims of the early Church scholars who laid the foundation that “Human life begins at the moment of conception”. In both cases the mistake is the same: deriving consequences from firm foundations isn’t the way problem solving works and the way forward is in rejecting dogma and embracing fallibilism. |

Archives

December 2023

CriticismThe most valuable thing you can offer to an idea Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed