|

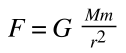

There are two great theories that explain the nature of physical reality. One is quantum theory and the other is general relativity. As science has regained some of its cultural cache over the recent years, physics has taken almost centre stage. If science were cinema, then physics is like James Bond - full of action and excitement with one of the longest lineages of any franchise. (By comparison, climate science is more like Jason Bourne - the newer kid on the block - a little more hip, maybe). Within physics the biggest star is Quantum Theory. It’s like the Daniel Craig of the Bond Franchise - cool, slick - it’s the physics you want to be seen with. But anyone who has studied physics knows that quantum theory isn’t all there is. There’s a lot more to physics. There’s physics stretching back to Sean Connery and Roger Moore. There’s "Newtonian" Mechanics and Thermodynamics and Electromagnetism. Each fan has their favorite. But if Quantum Theory is Daniel Craig, then General Relativity is Pierce Brosnan - a little older and a little less cool. But no less a Bond. Sometimes it is said that quantum theory explains the very small (things like atoms and smaller) while general relativity explains the large (things like planets and stars and galaxies). This is a gross oversimplification. A better point of distinction is this: quantum theory, in the form of the standard model - is a theory of the particles and forces at work in the universe. General Relativity is a theory of the spacetime background in which all those particles and forces interact - and so is an explanation of what gravity is. One great project of physics right now is to mesh these two physical theories together into a (so-called) "theory of everything". As of yet we cannot. There are some famous attempts: like string theory or "loop quantum gravity" - but these are speculative and so far have failed to make predictions that are testable in practice. We take quantum theory seriously as a description of reality. For example, the experiments of quantum theory are best interpreted as demonstrating that the electron is a particle (not a wave - despite some of the nonsense in text books, on websites and presented in lectures). Indeed it says that all matter is made up of particles: matter is lumpy. It exists in discrete chunks. And so too does energy - light too is a particle that exists in smallest possible units called photons. That all falls out of the standard model - the standard model is a theory of particles - and many experiments attest to this. Aside: particle does not mean "point like" according to quantum theory. Or, if it does, the fundamental entities of the standard model - the bosons, quarks and so on are neither point-like-particles nor waves but something more complex than either of those things. These fundamental entities are like "ink blots" (to use the terminology of David Deutsch in "The Beginning of Infinity") - this is due to Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle. Objects are extended through space at any instant of time. Motion in quantum physics is a complex thing compared to how it happens in "classical" mechanics. But I unashamedly use the word "particle" with the caveat: particles are not what you think they are. They are not "point like". This quantum theory leads to many astonishing consequences. I have mentioned one right there: particles more resemble ink blots that little indivisible spheres. And these ink blots are subject to a change in volume over time. I find that very bizarre. You may find the following ridiculous to the point of refusing to read further (though this is not an article, in the main, even about quantum theory) - and that consequence is that there must be a multiverse. I will not recapitulate that argument here and now. I urge the reader towards the work of David Deutsch, the creator of the theory of Quantum Computation and author, in particular, of "The Fabric of Reality" where I think the best, cleanest explanation of interference phenomena in terms of many-universes is made. You might also read this: https://www.bretthall.org/the-multiverse.html Or see my video series on all this for more than you could ever want perhaps: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLsE51P_yPQCQqJDb65AIVLads8PKxYuPm But now what about if we take the other great pillar of physics seriously - that of general relativity? What is the best interpretation of reality there? The interpretation there is that spacetime can be curved by matter. Both space and time are continuous entities - they do not have smallest units like particles do and moreover, the curvature of space around mass and energy is the explanation of gravity. That is to say: gravity is not a force. Since I began studying physics I have heard over and again how gravity is a force. Students in their first year of high school often hear about how forces are pushes or pulls and an example of a pull force is gravity. But even later you will hear university lecturers speak of gravity as a force. And the theory that gravity is a force is even used to practical effect. Newton’s Universal Law of Gravity is a theory which explains that gravity is a force. Science popularisers from Australian celebrity Dr Karl and even someone who should know much better - the English particle physicist Brian Cox - repeatedly refer to gravity as a force (although the latter may have a vested interest: as a particle physicist he may actually believe that the "graviton" is real, if undiscovered...). They refer to gravity as they refer to the other forces: as being fields. But this "force field" idea is an old, and false one if applied to gravity in the same way. Gravity is not like electromagnetism. There really do exist electric fields out there that exist between charged particles. There, particles really are "excitations of the field". This is explained by the standard model. But the standard model is not a theory of gravity. Newton’s Universal Law is a theory of gravity but we know it to be false. Einstein knew that Newton’s law of gravity simply did not “fit” with his Special Theory of Relativity. Special Relativity explains why no information can be transmitted faster than the speed of light. And yet Newton’s Law of Gravitation - which is expressed in a formula like this: (where the force F, between two masses M and m is a result of their product, divided by the square of the distance r, between them) says that the "force" in question travels from one place to another instantly in violation of what we know about information travelling at or below the speed of light.

This is because, Newton's Law, taken seriously, says that M will somehow “know” (better: “react to”) the amount of mass in “m” and vice versa in a way that does not depend on time. That is - the force is transmitted instantly. But that is in violation of special relativity. To be clear this was always a problem for Newtonian Gravity. And so was one major motivation for the General Theory - the current, and true, theory of gravity. In that theory there is no gravitational "force field". There is no force, period. There is no “graviton” despite the hopes of particle physicists everywhere. One has not been found and no theory that speculates about it does better than General Relativity. They do worse (if the standard is: make testable predictions that are correct and explain diverse phenomena in a coherent way). So we know gravity is not a force. Gravity is simply what happens to the path of an object moving near an object of sufficient mass. Its path becomes (apparently) curved. Curved in space - but straight in spacetime. In spacetime the path is always the shortest. How can a path curved in 3 dimensions be straight in 4 dimensions? This is hard and without the mathematics may seem absurd but Stephen Hawking in "A brief history of time" has one of the best analogies I have read on this. He writes: "This is rather like watching an airplane flying over hilly ground. Although it follows a straight line in three dimensional space, its shadow follows a curved path on the two-dimensional space." No extra "force" is required to "pull" the shadow of the aircraft into a curved path. But how can be it that so many - mainly particle physicists (or often (retired) engineers) - still seem to hope gravity is a force, and, in the case of professional physicists, speak about gravity as being a force while at the same time knowing it is not? Firstly, what does “know” mean here? It means what it always means when I use the word, when David Deutsch uses the word, when Karl Popper uses the word. It means what it should mean. It means "we have a good explanation". The best explanation of gravity: the best theory that we have of the phenomena - is understood by them. That is what “know” means. (full explanation of that here). The best explanation of gravity is Einstein’s General Relativity. It is the theory that enables GPS systems to work. So we’ve tested it again and again and it has always passed the test. Is it certainly true? No. But then no theory is certainly true (by which I mean: one feels that it is not possible that it could be false). But that is not what “we know what gravity is” means. It does not mean “we are certain” it means “we have a theory to explain it and that theory is the best theory we have" and in science this typically also means such a theory makes predictions that are better than any purported rival theory - including theories that do say gravity is a force - like Newton’s. And it explains the existence of entities that no other theory does and which themselves can in principle (if not always in practise) be observed (like say black holes or gravitational waves). To reiterate: the correct theory of gravity - that we know - General Relativity - says that gravity is the curvature of spacetime due to matter and energy. In curved spacetime, masses follow geodesics - straight paths. That is - they do not accelerate. And because they do not accelerate no force is needed to change their velocity (Newton's Second Law is still universally true, even given General Relativity. Observations falsify Newton's Law of Gravity: but not his laws of motion (see note [1] at the end of this article). Because in 4 dimensional spacetime they are not changing their velocity. They are following the shortest path between points in curved space around a mass. The shortest path in curved space near the Sun, for the Earth, is a very-close to circular orbit. And no force is required. And physicists know this. But why do they speak so loosely about gravity so often? In part I think it is because General Relativity is a classical theory. It’s a theory of continuous change. It’s not like quantum theory. And perhaps it doesn’t have the cool, sometimes mystical edge quantum theory unfortunately gets tarred with. According to General Relativity, space and time are smooth and continuous - you can divide space and time up infinitely. It seems many physicists - especially particle physicists - understand general relativity very well. They know it is the best theory of gravity. But they also hope it isn’t so. Or, as likely, they think there is another theory out there. And they are right to think there is another, better theory out there. There always is. There is a better theory out there than the standard model waiting to be discovered. But while they take the standard model seriously - unashamadly speaking of electrons and photons as particles - they do not seem to always take the general theory of relativity seriously because all too often gravity becomes a force again as though Newton’s theory was the last best word on the subject. There might also be something here to be said for the age old debate between the discrete and the continuous. In the Standard Model of Particle Physics - the theory that explains all the subatomic particles (including the Higgs Boson) and all the fundamental forces (electromagnetic, weak and strong) - there exist particles and forces. And the forces are mediated by particles too. On the other hand general relativity is about the continuous - smoothly varying curved space. It is thought that eventually the two must be unified in some way by a deeper theory that explains how both arise - but how? Currently there is no definite solution to this. But my guess is that most physicists generally seem to think that gravity will be "quantised": in other words, quantum theory will in a sense “win out” over general relativity. The discrete will trimuph over the continuous. But there is no reason to think this (it's a form of induction: it has happened in the past, and the past (so the argument goes) resembles the future so we should expect more and more that the discrete overtakes the continuous. Now never mind that this latter point simply isn't true: the former point that the past resembles the future is also completely wrong. Yesterday isn't much like today (if it is, change your life!) and seconds after the big bang look totally different to what we have 13.7 billion years later. So the past doesn't resemble the future making so called "induction" quite irrational.) So there is no reason to think the discrete will win out (or the continuous, either, of course). In that situation - the very situation we are in - we should take each theory seriously. When we speak about electrons and photons - we should refer to them as particles. And when we refer to gravity - we should not speak of it as a force. Yes, it's true: some physicists hope (perhaps that's the right work) and prophesy (that is the right word!) that some day gravity will fall under the umbrella of quantum theory. There will be, they argue, a quantum theory of gravity that makes spacetime into some type of discrete entity. That may well happen. But no one knows yet! Not even the expert physicists and science communicators in this area. And they should stop pretending that they do. I abhor appeal to authority - and that logical fallacy deserves its own post - but I know some are persuaded. And persuasion through correct explanation is my aim here so if you are not persuaded by my words then perhaps those of some others will assist. Here are some other places that make some nice clear statements about gravity not being a force: From the “howstuffworks.com” article on Gravity: “gravity is not a force. It's a curve in space-time”. A Canadian Newspaper even had an article on this whole issue once. Cornell University's Ask an Astronomer addressed the Gravity is not a Force thing too. And here is an online lecture from Florida State University on General Relativity. By the way, some people claim Einstein did not say that gravity was not a force. Of course there were many things Einstein did not say. But what he did say was what gravity was (curved spacetime!). But besides, it does not matter what Einstein the person did or did not say. Authority - even of great thinkers - even talking about their own theories - is not what matters. It matters what we understand today. Notes: [1] In order to explain observations like how spiral galaxihttp://phys.org/news/2007-03-newton-2nd-law-violated-earth.htmles rotate, some have suggested what amounts to an ad-hoc change to Newton's Laws. These changes are called "Modified Newtonian Dynamics" (MOND). For example here: http://phys.org/news/2007-03-newton-2nd-law-violated-earth.html The problem is that MOND changes Newton's Law of Gravity (and other laws) in order to explain phenomena that usually fall under the category of "dark matter mysteries". But those mysterious motions of galaxies individually and an in clusters - due we believe to dark matter we have not yet detected - are mysteries only in light of General Relativity. MOND would have to be MOEG (Modified Einsteinium Gravity) - we already know that Newton is false, so any theory that attempts to take it as literally true, and then arbitrarily modify it in order to mathematically predict (but not explain) the motion of planets - does no better than assuming the solar system is literally geocentric while adding epicycles to the orbits. So, few people take MOND seriously...because it's not actually an explanation.

9 Comments

|

AuthorBrett Hall ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed